Volcano appreciation

Volcanoes are vital to many communities. They can be a crucial source of water, provide fertile soil for agriculture, and provide tourism drawing in skiers, hikers, and general admirers.

While it is important to appreciate the resources and benefits volcanoes can provide, it is also important to remember that many of them can behave dangerously.

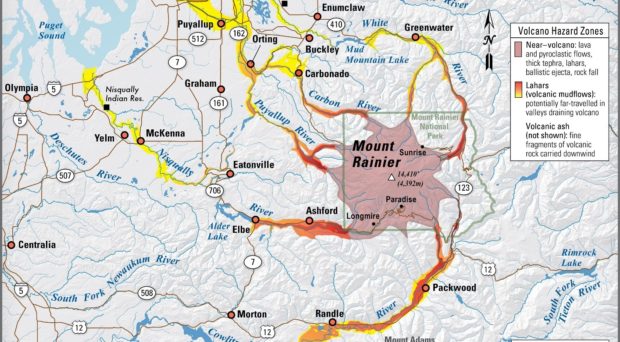

Our research focused on Mount Rainier/Tacoma, part of the Cascade Range in the northwest of the United States, and one of the most dangerous volcanoes in the world.

One of the main risks is lahars—volcanic mudflows which could directly impact over 150,000 people.

How do we learn about volcanic risk and preparedness?

People often learn about volcano risks from popular media (like movies or video games), news media, or friends and family.

However, this information can vary in accuracy, doesn’t necessarily present the full range of volcanic hazards (which extend well beyond sudden, explosive eruptions of molten rock), and can lead to fatalism—if all you hear about volcanoes is the damage and harm they cause, you might start to think such outcomes are unavoidable.

Cue, public education

For decades, many dedicated people have worked to inform communities about the natural risks they face and, crucially, what they can do to reduce how much they’ll be impacted when something bad happens.

However, our brains have developed tricks and shortcuts which help us deal with things that scare us, including:

- Risk prioritization—people tend to prioritize lower impact, higher probability risks like car accidents over higher impact, lower probability risks like volcanic eruptions;

- Biases like fatalism (mentioned above), unrealistic optimism (where people think they’ll be fine, even if everyone else isn’t), and normalization bias (where people assume that future events will be like past events);

- Social cues—we look to those around us because chances are if everyone is doing something it’s a good thing for us to do as well.

To overcome these challenges, it helps to understand which ones are most influential. This is where our research comes in.

To find ways to better encourage communities around Mount Rainier, and similar communities near volcanoes, we explored a range of factors which previous research tells us are probably relevant, to see which ones are going to be the most important for us to address when we talk to these communities.

Our survey

Over 800 people from the Mount Rainier area, mostly Orting and Puyallup, responded to our survey. Interesting findings covered demographic, geographic, behavioral, social, and cognitive factors, highlighting the complexity in understanding people’s intentions to prepare and attitudes around lahars.

Women felt less prepared and had higher intentions to prepare than men; these differences appear to be motivated by women seeing the potential impact of a lahar as more severe than men, rather than differences in how likely it is a lahar will occur.

Interestingly, when looking across the whole sample people, who saw lahars as more likely had stronger intentions to prepare and were more likely to have prepared an evacuation kit but there were no differences based on impact perception.

These findings demonstrate the challenge of communicating the risks posed by natural hazards.

The people in our sample who neither live nor work in a lahar hazard zone felt the most prepared, perhaps reflecting a key risk reduction behavior of avoiding dangerous areas when possible.

Interestingly however, these people were more likely to have an evacuation kit, highlighting the challenge that there are typically many different behavioral motivations.

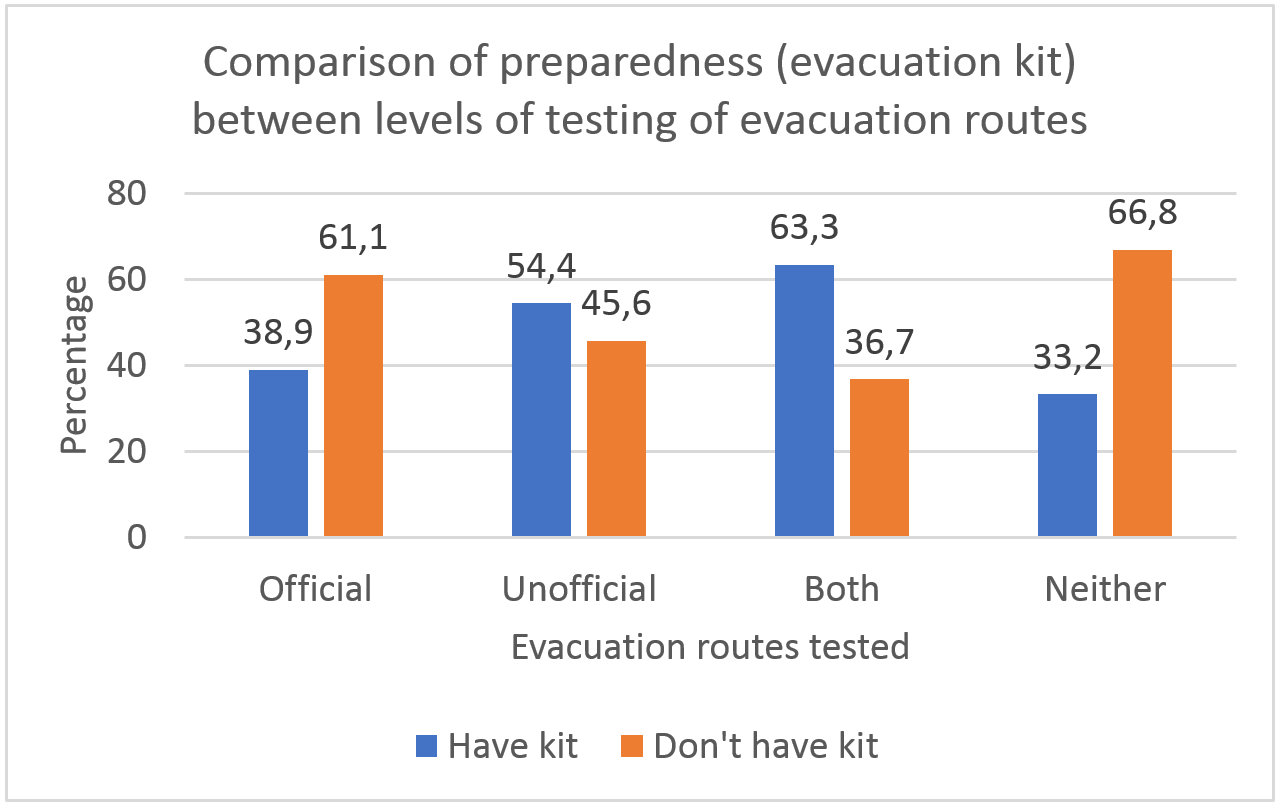

Other factors which were associated with feeling more prepared included participating in evacuation drills and testing evacuation routes.

These behavioral factors were also associated with higher self-efficacy, self-perceptions of capability and capacity to undertake a behavior (in this case, protect yourself from lahar impacts).

In particular, those who had tested “unofficial” evacuation routes showed the most positive beliefs and behaviors.

One limitation of our type of study is that we can’t say the direction of the effect; this is a good opportunity for future work.

What does it all mean?

As well as helping to improve our broad understanding of why people prepare for hazards like lahars, our findings offer ways for local public education efforts to approach the ongoing challenge of encouraging preparedness.

Key suggestions include the continued use of evacuation drills and ensuring where possible that communication is tailored to diverse groups in the community.

Comments