In 2020, the United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF) reported that 22% of children under five years old were stunted worldwide. Children who are stunted suffer from both physical and cognitive impairments and are therefore disadvantaged in terms of their academic potential and future earnings. Stunted children also have an increased risk of non-communicable diseases (NCDs) such as cardiovascular disease, diabetes and cancer in later life, which is often termed the double burden of malnutrition.

Helminth infections are strongly linked to poverty and include several different parasitic worm species, with the biggest group, known as soil-transmitted helminths (STHs), affecting around one and a half billion people globally. In the current context of the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) and Global Nutrition Targets 2025, the numbers of stunted children and people suffering from helminth infections worldwide remain alarmingly high.

Human helminth infections are often overlooked in the global health sphere, since they cause relatively low mortality compared with other more high-profile diseases, although they are significantly disabling. Helminth infections are classified as neglected tropical diseases and as the name suggests, diseases in this category tend to suffer from a lack of funding, awareness and advocacy. Helminth infections are not necessarily confined to the gut, with several species injuring the liver, lungs, bladder and sometimes even the brain. Those affected may experience symptoms ranging from anaemia, blood in urine and chronic diarrhoea to intestinal blockage, rectal prolapse and cancer in more severe cases. Since these infections are so common across many of the typically most impoverished populations of the world, treatment usually involves mass drug administration (MDA) during which people are given anthelmintic (deworming) tablets without being tested first, and this usually takes place in schools for practical and logistical reasons.

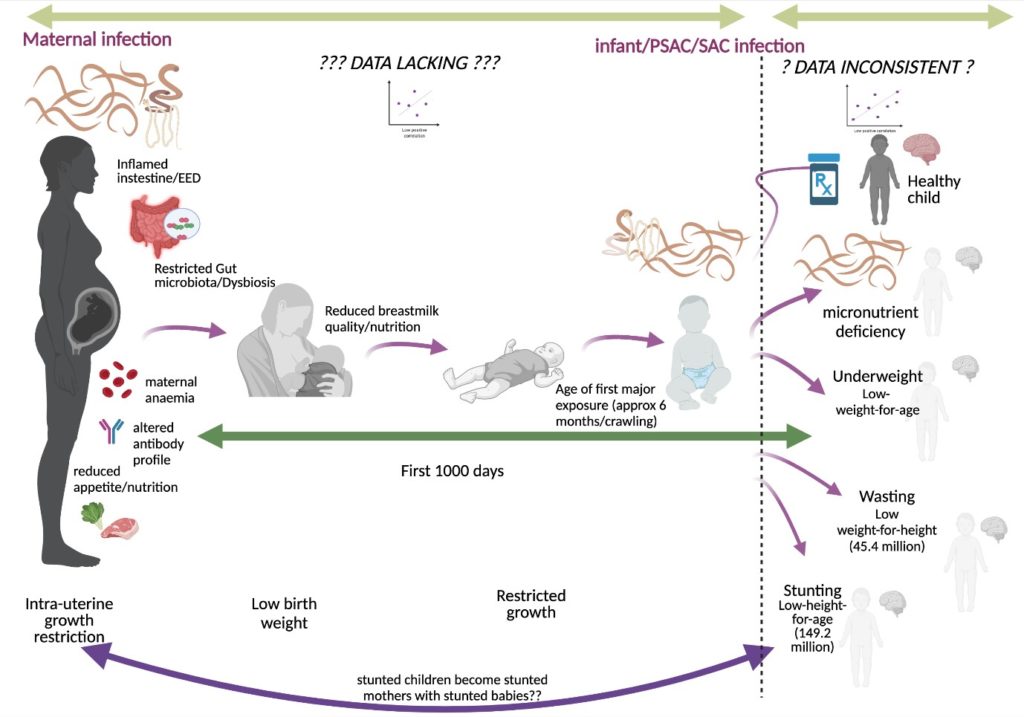

Due to this school-based approach, infants and pre-school age children (less than five years old) have, until recently, not been treated. The omission of these youngsters from treatment programmes was partly due to a lack of licensed medication for this age group (although this is no longer the case, and further paediatric formulations are currently in preparation) and because these age groups were previously not considered high risk. Yet we know that when infants start to crawl and become mobile at around six months of age, they are exposed to their environment and therefore disease risks, in much the same way as older children and adults. Furthermore, recent findings suggest that infants and young children may be especially vulnerable to both becoming infected with, and at greater risk of morbidity from, helminth infections due to a combination of their hygiene and play habits and their immature gut microbiome.

Pregnant and breast-feeding women have also historically been excluded from deworming programmes originally due to safety and licensing concerns, although these worries have since been alleviated and indeed are now specifically targeted for treatment. The first 1000 days of a child’s life are crucial for their physical and cognitive development. This period stretches from conception to a child’s second birthday, yet the idea of possible in utero stunting is only recently starting to gain traction. For example, a low birth weight (<2.5kg) or very low birth weight (<1.5kg) baby might be the result of in utero stunting. Ensuring that pregnant and breast-feeding women in endemic areas receive deworming treatment therefore has the potential to impact early childhood stunting, not forgetting the benefits of treatment for the women themselves, such as reducing anaemia.

Our systematic review aimed to elucidate whether the currently available literature evidence suggests that helminths cause physical stunting in children. We aimed to include a wider range of helminths (STHs including Strongyloides stercoralis, schistosomes and food-borne trematodes) and a wider range of study designs than previous work on this topic, as well as studies in which pregnant and breast-feeding women received deworming treatment. Overall, we found no significant evidence that helminths cause physical stunting in children.

However, our main finding revealed the extremely limited data currently available for the key demographic groups of infants and pre-school age children, as well as pregnant and breast-feeding women. Our review therefore highlights the need for future research to address these crucial evidence gaps in relation to childhood stunting and helminth infections, and in particular to recognise the role of maternal health and possible in utero stunting. Thankfully there is now a major multidisciplinary programme, the UKRI GCRF Action Against Stunting Hub, which has been initiated with the aim of achieving precisely this – from epigenetic to socioeconomic perspectives. Scientists are also beginning to learn more about the complex interplay of a range of direct and indirect risk factors for stunting, one of which is that of potential helminth-gut microbiome interactions. These exciting areas are sure to reveal many important insights regarding our understanding of the causes of, and ultimately the prevention of, childhood stunting in the future.

Indeed, as the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic continues, existing health inequities are becoming uncomfortably clear. Having recently celebrated World NTD Day 2022 and the launch of the World Health Organization guideline on control and elimination of human schistosomiasis, it is vital that we continue to advocate for vulnerable populations worldwide, in order to improve not just physical health, but quality of life as well.

The study featured in this blog post was published in the LCNTDR Collection: Advances in scientific research for NTD control, led by the London Centre for Neglected Tropical Disease Research (LCNTDR). The collection has been publishing in Parasites & Vectors since 2016, and releasing new articles periodically. This series features recent advances in scientific research for NTDs executed by LCNTDR member institutions and their collaborators. It aims to highlight the wide range of work being undertaken by the LCNTDR towards achieving the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals as well as supporting the objectives of the World Health Organization road map for neglected tropical disease 2021-2030.

The study featured in this blog post was published in the LCNTDR Collection: Advances in scientific research for NTD control, led by the London Centre for Neglected Tropical Disease Research (LCNTDR). The collection has been publishing in Parasites & Vectors since 2016, and releasing new articles periodically. This series features recent advances in scientific research for NTDs executed by LCNTDR member institutions and their collaborators. It aims to highlight the wide range of work being undertaken by the LCNTDR towards achieving the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals as well as supporting the objectives of the World Health Organization road map for neglected tropical disease 2021-2030.

The LCNTDR was launched in 2013 with the aim of providing focused operational and research support for NTDs. LCNTDR, a joint initiative of the Natural History Museum, the London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine, the Royal Veterinary College, the Partnership for Child Development, the SCI Foundation (formerly known as the Schistosomiasis Control Initiative) and Imperial College London, undertakes interdisciplinary research to build the evidence base around the design, implementation, monitoring and evaluation of NTD programmes.

You can find other blog posts in the series here.

Comments