The World Health Organization and the Centers for Disease Control recently declared that SARS-COV2 is transmitted through aerosol droplets. We’ve known this critical little tidbit for over a year, but does this declaration finally make it true?

In many respects, the answer is yes. When something is OFFICIALLY ANNOUNCED, resources start flowing to address the OFFICIAL PROBLEM. Of course, less so with COVID-19, since it turned into a bonified pandemic. But for many other diseases, this is a real issue. Chagas disease, for example. Last month we celebrated a day designated by the World Health Organization to call attention to this wide-spread, parasitic disease afflicting millions of people in almost every country in the western hemisphere.

Despite millions of people suffering from Chagas disease, a life-long parasitic infection that can lead to heart failure, the disease is not well-known in the US because it is officially NOT TRANSMITTED HERE. Despite 112 years of research on the disease, there is no vaccine (and there certainly is no Operation Warp Speed for a disease that is NOT HERE). The parasite that causes Chagas disease, Trypanosoma cruzi, transmits in a number of ways, including through contact with the feces of triatomine bugs. Like HIV, measles, and likely COVID-19, Chagas disease is a zoonotic disease, meaning we share it with animals.

Zoonotic diseases can jump from animals to people and back; they are a symbol of the interwoven nature of planetary and human health, and a symptom of the continual human destruction of non-human habitats. Chagas disease is particularly complex in that it is caused by a parasite, spread by a bug, and hosted by mammals, including us. As a result, the disease transmits across within and between many different landscapes- forests, villages, and everything in between.

There are a lot of assumptions surrounding where T. cruzi transmission happens, and by what. Most of these assumptions are based on an absence of evidence, starting with Chagas disease being a rural disease of poverty. While, yes, Chagas disease is transmitted in rural areas, the disease is also found in urban areas. T. cruzi– infected kissing bugs have been found in cities all over Latin America- Sao Paulo, Rio de Janeiro, Cochabamba, Arequipa, Caracas– and the list continues to grow.

The second assumption is that kissing bugs are a ‘south of the border’ problem. Studies of triatomines in the United States are on the rise, and it’s not because the bugs hitchhiked here with Central American immigrants, despite what some news outlets might like to tell you. The bugs have been here for millions of years. The thing is that it’s only now that people have started to get interested, which brings about a third Chagas tenet, although this one is generally true – if you look for triatomines, you will find them. Kissing bugs in the US began to receive a lot of attention in 2009, when bomb-sniffing dogs deployed to Iraq started showing cardiac symptoms due to T. cruzi infction. Since Chagas disease is transmitted strictly in the Americas, attention shifted to where the dogs had been trained- San Antonio, Texas. Naturally, the US government threw piles of money at the problem. A series of follow-up surveys revealed four species of kissing bugs living in and around military dog kennels in Texas, and dogs infected with T. cruzi were found all over in Texas. A slew of new kissing bug studies followed, which are still happening. Just this year, a study of 476 government working dogs in 40 US states found a T. cruzi seroprevalence of 12.2% (58/476). These studies continue to reveal that kissing bugs are all over the place in human-dominated areas (i.e., not just ‘natural areas’) of Texas and the greater US. Ironically, 2009 was the 100th anniversary of the discovery of T. cruzi by Carlos Chagas in Minas Gerais, Brazil. I can’t help but wonder what all the money thrown at Chagas in military pups could have done for the millions of people suffering from Chagas disease throughout Latin America and the Caribbean.

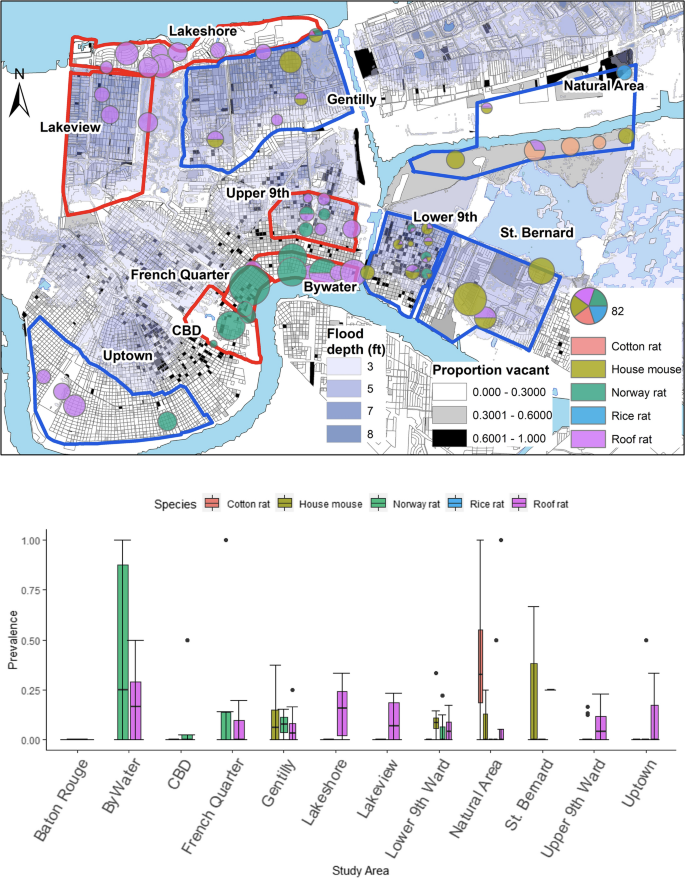

But we’re not here to talk about US military spending and we’re not here to talk about Texas. We’re here to talk N’awlins, the city of jumblaya, jazz, and… kissing bugs? In a city to which tourists flock to soak up its one-of-a-kind food, arts, and culture scene, it is particularly intriguing that recent studies are revealing that apparently kissing bugs and T. cruzi-infected mammals want to be there too. In their work recently published in Parasites and Vectors, Ghersi et al. found 11% of rodents to be positive for T. cruzi, including those sampled from tourist hotspots like the French Quarter. And only a few weeks before, Dumonteil et al. reported 25% of shelter cats sampled in southern Louisiana to be positive for T. cruzi. In another study, 45 bugs collected from human homes and animal shelters were analyzed molecularly to determine the hosts on which the bugs were feeding, and they found the bugs to be feeding opportunistically across a wide range of species, including birds, reptiles, amphibians, and mammals, both domestic and synanthropic. Finally, another study found out of 195 sequences from Triatoma sanguisuga collected in and around human residences in Orleans Parish (i.e., county), human blood meals were found in 162 of them.

Most importantly, the predominant host species of the bugs were humans and their animals. This finding is making me think that yet another Chagas dogma is going to be turned on its head, which is that vector-borne T. cruzi transmission in the US is strictly enzootic. I predict that greater access to molecular tools allowing for identification of numerous blood meal host species, coupled simply with more people looking for the bugs, will shift these Chagas transmission dogmas into evidence-based acceptance that T. cruzi is transmitted to humans by kissing bugs in the United States across multiple landscapes, including urban areas. No, it is not that frequent, and no, there is no need to freak out. But, as I have written about before, these dogmas and labels of, ‘this happens here but not here’ and, ‘to them but not us’ are not helpful. These labels serve as barriers to accessing resources and raising awareness for those who need to be aware (medical professionals, people living in areas with the bugs). We as a global health community need to stop slapping these labels on and filing them in the ‘forever’ category, and start accepting that transmission happens where it happens. Maybe then we will learn to be light on our toes and someday perhaps respond in time.

Comments