Although this dog disease is common throughout the world, the only cases of canine babesiosis diagnosed in the UK have been in infected dogs imported from abroad. Babesiosis was not considered to be transmitted in Britain. However, this year four dogs contracted the disease despite never having been outside the UK. All four lived in Harlow, Essex and were regularly walked in the same area of wasteland. Three of the dogs treated at the Forest Veterinary Centre in Essex survived, but one did not.

The parasite

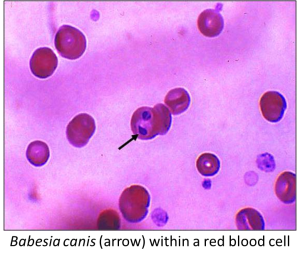

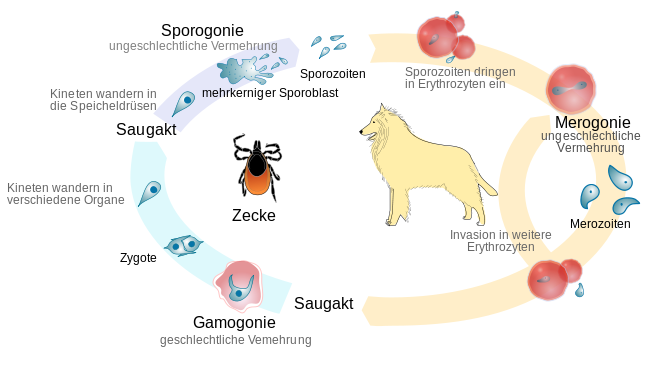

Canine babesiosis is caused by infection with a unicellular parasite similar to the malaria parasite. The parasite belongs to a worldwide group of vertebrate blood parasites in the genus Babesia that have significant veterinary, medical and economic importance. They are all transmitted by ixodid (hard) ticks.

Dogs are infected via the bite of an infected tick and mothers can transfer the parasite to their pups. The sporozoite stage of the parasite is present in the tick’s saliva and is transmitted to the dog as the tick injects its saliva into the bite site. The parasites invade red blood cells, their pear-shaped appearance giving rise to the name, piroplasm. They multiply, eventually causing the red blood cell to burst and release the piroplasms to invade new red blood cells.

The symptoms

As blood cells are destroyed anaemia develops in the dog (as indicated by pale coloured gums) and haemoglobin is released which gives rise to jaundice-like symptons. Other symptoms include loss of appetite, weight loss, lethargy, fever, enlarged abdomens and red-brown urine.

The vector

This is the tick that appears to be responsible for the outbreak of canine babesiosis in Essex. The occurrence of the parasite in an active population of D. reticulatus ticks was established in March this year by a team surveying the cycle path in Harlow where the infected dogs were exercised. It has recently been reported to be associated with canine babeosis in Southern Italy.

Dog protection

Ticks must feed for at least 24 hours to pass the infection on, so dogs that have been in woodlands or rough areas where ticks might exist should be checked daily and ticks removed with forceps. There is no vaccine against canine babesiosis but anti-tick measures can be employed to help protect dogs. These include protection via acaricide sprays or the wearing of impregnated collars.

The Big Tick Project was launched in April. Led by Richard Wall of the University of Bristol, the launch was publicised by television presenter Chris Packham. The project aims to increase awareness of tick-borne diseases amongst dog owners. Ticks sent in by vets taking part in the project will be analysed for the presence of parasites including Babesia and the agent responsible for Lyme Disease, caused by bacteria of the Borrelia type, which can infect dogs as well as humans causing lethargy, fever and lameness.

In addition to this, Public Health England has been running a tick surveillance scheme since 2005. It aims to monitor the distribution and seasonality of ticks nationwide and record the incidence of exotic tick species.

Other forms of babesiosis

Different species of Babesia parasites can infect mammals including cattle, where they cause serious disease. Several species of Babesia infect humans, Babesia microti is the most common in Northern America and Babesia divergens in Europe. Babesiosis, considered to be an emerging zoonosis (a disease transmitted from animals to humans).

Interestingly, the journal Ticks and Tick Borne Diseases recently published a report of babesiosis occurring in chinstrap penguins in the Antartic. The tick vector, Ixodes uriae, is the only tick present in the Antartic.

Major concerns

Veternarians expressed grave concern when the regulations governing the import of dogs into the UK were relaxed in 2005 in compliance with EU regulations concerning the free movement of animals. Sadly it appears that their predictions have come true and this relaxation has led to the import of a tick borne disease new to the UK, along with the dogs. Coupled to this the recent mild, wet winters in Britain have led to an increase in tick populations. Vets who initially treated the infected dogs have pointed out that the thousands of eggs laid by an infected female tick will all carry the parasite so canine babesiosis could rapidly spread to other areas of the UK.

At the risk of “shutting the stable door after the horse has bolted” perhaps it is time to rethink the relaxation of regulations regarding the free movement of dogs between the UK and mainland Europe.

Dear Prof. Hilary Hurd,

It is now a year since Harlow Council fenced off the meadow where the Ornate Dog Ticks thought to be responsible for Canine Babeosis in 4 dogs which had never been abroad.

The 7 foot high building site interlocking fencing erected will have kept people and dog-walkers out of the area. The local paper has not reported further cases.

However I am a Field Officer for the Harlow Badger Group, and while this fence would keep out humans I would not put it past any badger to breach this. An adult badger is about the same weight as the dogs infected last year. There is an established sett within roaming range of the fenced off area.

Do you think it is likely that Babesia Canis could affect Badgers (Meles meles), or are they too far apart taxonomically?

Dear Lawrence,

Thank you for the information concerning the enclosure of the meadow. That is good news.

I have been unable to find any evidence that B. canis can infect badgers so I think you have nothing to worry about. This species appears to be specific to dogs. However other species of Babesia do infect badgers. You might be interested in this article https://www.blogsanidadanimal.com/EU/wp-content/uploads/2017/01/11_BARANDIKA.pdf.

Dear Prof. Hilary Hurd,

Thank you for the reply and the link.

I only did Biology, Physics and Chemistry to “A” Level so it will take me a little study to grasp this. What is immediately interresting is the new piroplasm related to B. Vulpes found in a badger in Spain. (Gimenez et al 2009).

It seems that it does not take much of a change in the genotype of a piriplasm for the phenotype to cross the species boundary.

Do you know if there is anything sensible that can be done with a tick infested area, or would you have to exterminate all the arachnids in the area; would insects be affected, such as honey bees.

Harlow is a Garden Town similar to Milton Keynes with much green areas and many nature reserves within the town, consequently dog ownership is quite high.

I will raise this at the next Harlow Diversity Group meeting as well as the Badger Group.

Thanks again

Laurence Norwin-Allen