In 1978 Louise Brown, the world’s first ‘test-tube baby’, was born after her parents underwent successful in vitro fertilization (IVF). Since then over five million IVF babies are thought to have been born around the world.

I was also born in 1978 and shortly after each of my significant birthdays –18th, 21st, 30th – the media turned to Louise to mark the passing of time since IVF was first performed. Attitudes to IVF have changed and it is now celebrated as a procedure that brings happiness to parents who may otherwise not be able to have their own biological children.

It is hard to imagine now that in my lifetime many have stood against the technology, believing humans were ‘playing god’, or interfering in the natural order of things. Indeed today we are more inclined to discuss the merits of single vs multiple embryo implantation during IVF than whether it is right or wrong.

Yesterday the world’s eyes were on the UK Parliament, which voted to amend the Human Fertilisation and Embryology Act 2008 to allow mitochondrial replacement IVF techniques. This offers hope to parents wanting to have children free of rare diseases. This is not an across-the-board green light, but would mean an expert panel can consider, on a case-by-case basis, requests from couples who want to use the technique.

What is mitochondrial replacement IVF?

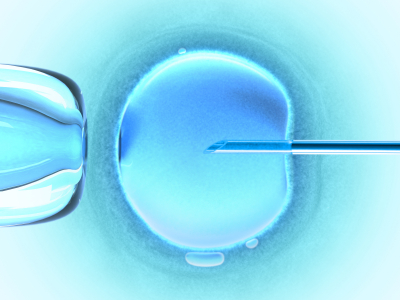

Popularly known as ‘three-parent babies’, the technique involves transferring the nucleus from a woman’s egg to a donor egg where the nucleus has been removed but the healthy mitochondria remain, and then fertilizing that donor egg. It was developed by a team at Newcastle University and published in April 2010. Full disclosure – I was involved, in my last job, with the publicity around the original research article.

What are mitochondrial diseases?

“Mitochondrial disease is horrible and there is no treatment for it,” stated Frank Dobson, Labour MP for Holborn and St Pancras. He went on to argue that the Newcastle team did not start with this risky, novel approach. They have been working for 20 years to try to treat mitochondrial diseases.

“The best that it has managed to come up with after all these years is helping parents cope with the horrible symptoms before their children fade away and die. As has already been said, the team has decided that if it cannot come up with a treatment—and it is still trying—it would be better to prevent the disease arising in the first place because prevention is better than cure.”

Mitochondrial diseases are caused by dysfunctional mitochondria – the batteries of the cell that convert energy from food in order to power cell function. They can be caused by mutations in mitochondrial DNA that affect the ability of the cell to function normally.

Mitochondria is of interest to many fields of biology – from health and lifespan to cell signalling and cell death. BioMed Central journals have pulled together relevant content into an article collection here.

What impact does this ruling have?

Professor Doug Turnbull, who leads the Newcastle team, said yesterday: “I’m delighted for patients with mitochondrial disease.

“This is an important hurdle in the development of this new IVF technique, but we still have the debate in the House of Lords, and importantly the licensing by the HFEA. Finally, I think the quality of the debate today shows what a robust scientific, ethical and legislative procedure we have in the UK for IVF treatments. This is important and something the UK should rightly be proud of.”

And finally…

In my short lifespan I’ve seen huge changes in attitudes to IVF and developments in both this and other embryonic research. I’ve been lucky enough in my career to meet the late Robert Edwards, who pioneered the technique, and to publicise much high-profile embryonic research.

The debate yesterday (you can read the transcript here) in the House of Commons was carried out in a thoughtful and rational manner that impressed me.

Frank Dobson, compared the debate with past discussions about embryonic research and IVF: “The objections that have been brought out today, and in previous discussions, about mitochondrial disease are identical to those that arose when Louise Brown was brought into this world at Oldham General Hospital as a result of the risky work undertaken by Steptoe and Edwards and Jean Purdy.”

IVF has brought about much change in our society and brought hope into many lives. I feel that mitochondrial transfer is the next stage on this journey, and stands to benefit families who up to now had little or no hope of having healthy children.

Further reading:

Article collection on IVF from Reproductive Biology and Endocrinology: https://www.rbej.com/series/IVF

I think that ‘Mitochondrial transfer’ is a misleading term, because, as you describe, the procedure is actually nuclear transfer, of the mother’s egg-nucleus to an enucleated egg from another woman, with all its cytoplasm and organelles, including the mitochondria, with their own mitochondrial chromosome from this other woman, the third parent.

I absolutely agree that mitochondrial disease should be avoided by creating a zygote (fertilized first cell of the new person that it is hoped to become) with intact mitochondria that do not have the damaging mutation in the mitochondria of the mother’s eggs, but the method that has now gained approval by the UK parliament ignores the biological objection voiced not only in the UK parliament and on Radio 4 by Jacob Rees-Mogg but also, I believe, by an alarmed group of Italian MPs.

The objection is that this procedure makes a genetic change that will be passed on to future generations, and that this is creating a new type of human being with DNA from three people. The Italian MPs were concerned that this would change the human species forever.

Actually it should be possible to avoid this problem. The nuclear parents are going to be healthy people, and it should be possible to use a somatic cell from one of them instead of an egg from a second woman. Dolly the Sheep was created from a somatic cell, and that was about twenty years ago, so it should be possible to fertilize the egg from the mother with the father’s sperm and then transfer the fertilized (zygote) nucleus to a somatic cell from one of the two parents. The somatic cell might need to be reverted to a stem cell first, but this obviously isn’t impossible.

It may be that occasionally a mitochondrion from a sperm gets into an egg and survives, but usually this does not happen, and most, if not all of us, have in all our cells, mitochondria that come only from our mother, so obviously it would be preferable for the somatic cell to come from the mother. If the mitochondrial mutation was in one of her ovaries and her somatic cells were free of mutated mitochondria, there would be no problem. However, in some cases, though healthy herself, she might be a ‘mosaic’, having some unmutated and some mutated mitochondria, and in this case, it would be preferable to use a somatic cell from the father. The child would then have mitochondria from the father rather than the mother, which is not the usual biological case, but at least there would be no third parent.

This procedure might be technically more difficult than the procedure that has, I believe rather rashly been approved so rapidly in the UK, and might take a little while to perfect to a safe standard, but it would avoid the ethical, biological and legal problems that the currently-approved method creates. I cannot understand why it has not been discussed.

The one situation in which none of the objections to the approved procedure would apply, would be that the donor of the enucleated egg would be a relative of the mother through the female line, because her mitochondria should be identical to those of the mother. However, once the currently-approved method takes off, I’m sure this would not always be the case.