We know that the environment is important for determining where species – both hosts and parasites – can live and thrive. But characteristics of hosts – such as their age, immune response, or sex – are also important for determining infection and disease. When more hosts become involved – for example with vector-borne diseases and other complex lifecycle pathogens – the complexity of these interactions only increases. Sometimes the intermediate host habitat is the best predictor of disease and other times it’s the host immune system that is important for predicting disease. Teasing apart drivers of disease is difficult, but essential in order to design sustainable interventions and effective control strategies.

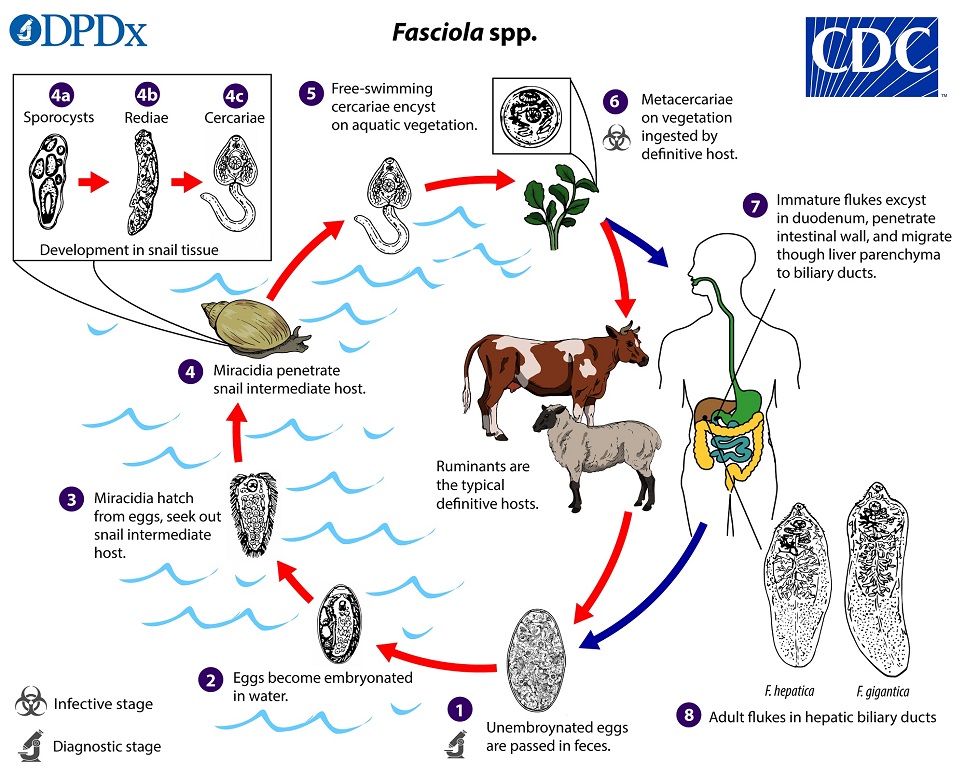

Liver flukes are parasites that undergo complex life cycles and can infect a diversity of animals. Humans can become infected with Chlonorchis or Opisthorchis species by eating raw or undercooked fish and seafood. Another genera, Fasciola, is found in over 70 countries around the world and infects humans and domestic ruminants, mostly cows and sheep. Fasciola hepatica, also known as the common liver fluke, requires a definitive host (ruminants such as cows) and a snail intermediate host (see life cycle below). This parasite has can lead to serious negative health consequences in domestic animals, and this likely extends to wild ruminants as well.

In a recent study, scientists investigated the impacts of the habitat and individual host characteristics on liver fluke infections in the Scottish Highlands. They focused on red deer (Cervus elaphus) and the common fluke (Fasciola hepatica). The goal of the study was to determine what host features (age, gender) and habitat features (land cover, streams, rainfall) might influence whether or not a deer is found infected with F. hepatica. Liver flukes can cause serious health consequences in domestic animals, and this likely extends to wild ruminants as well. Understanding where and which animals are infected is important for improving herd health.

In order to measure infection by liver flukes, the scientists used deer that were hunted across nine Scottish Highland Estates. Hunters aided in the study by collecting fecal pellets from the carcasses and recording the sex, cull date, age category, and location. The scientist then used these fecal samples in a competitive ELISA to measure antibodies (a specific immune response) to liver flukes. This can mean the animal is currently infected with flukes or has previously been infected with them.

For each location where a sample was obtained, the authors collected several habitat characteristics from publicly available data sources. They assumed that each deer roamed up to 2 km from the location it was found in and used this to evaluate each deer’s home range habitat characteristics. The landscape on these estates are either smooth grasslands, heather moor or blanket bog. The proportion of each land cover type was determined for each home range. The total length of streams was also calculated. This was included to help account for potentially suitable snail habitat. Although the snail vectors are not usually found in running streams, they are often found adjacent to these water sources and thus length of streams might be a useful measure of total snail habitat. Lastly, the authors also collected total rainfall (moisture is important for sustaining parasites) and number of days above 10°C. At 10°C or warmer, the metacercariae can develop and snails can grow, but below that temperature it is unlikely to support intermediate hosts, and parasites are unlikely to infect definitive hosts.

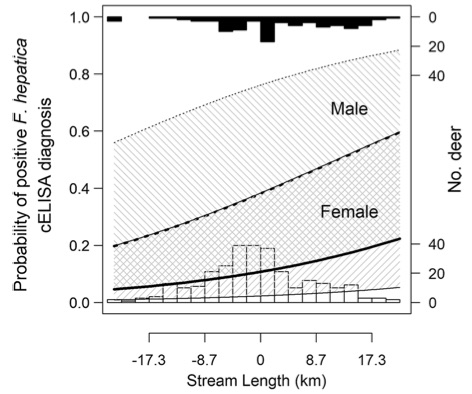

Over 600 animals were observed across two years. In the 2012-2013 year, about half of the variation in infection could be explained by the estate where the animal was found. However, in addition to this environmental predictor, the total length of stream within a home range was positively correlated with a positive diagnosis, suggesting increasing streams within a home range increases parasite exposure. Additionally, the authors found that males were more likely to be infected than females. While these findings suggest that both host and the environment are important, these variables did not explain all of the variation in infection seen.

The jury is still out as to why some deer have flukes and others do not, but it is clear that it is a common parasite found throughout the Scottish Highlands and both host and the environment are important. Future work to help elucidate where snail intermediate hosts are in the environment, where metacercariae can persist and infect hosts, and why some deer don’t seem to become infected will help to unravel the drivers of disease in this complex system.

Comments