Why ectoparasites?

Ectoparasites are organisms that live on the external surface of an organism (the host), from which they obtain their sustenance. The inflicted harm on the host can range from being a mere nuisance to life-threatening health conditions. Ectoparasite biology and host dependence is highly diverse. Some ectoparasites, such as lice, are permanent parasites that are highly dependent on a single host for survival and show a high species specificity, whereas others, for example ticks, only form temporary relations with their hosts and are more general in their choice of food source. Feeding on several hosts can lead to pathogen transmission between individuals, within one species, but also between wildlife, livestock and humans and therefore attracts particular attention.

Why lemurs?

The nocturnal mouse lemurs are the world’s smallest primate species, are endemic to the island of Madagascar, and have become flagship species for conservation. Faced with poverty, political instability, population growth and, as a result, human encroachment into wildlife habitats, the natural distribution range of mouse lemurs is continuously declining and the majority of the currently recognized 24 species are today listed as Endangered by the IUCN Red List.

Parasites and hosts have co-evolved for millions of years and may exist in a delicate balance with each other. Different factors, such as climate or host behavior are known to influence parasite intensity and mechanisms of adaption and evasion are pushing and pulling on either side. If this balance is disturbed, the negative effect of parasites may not be limited to the infected individual, but reduced survival and reduced reproduction can lead to severe effects on a population level. Therefore, parasitic infections have become a major concern in conservation biology.

Our international interdisciplinary German-Malagasy research team with experts from parasitology and zoology investigated ectoparasite communities of two Microcebus species (the Grey Mouse Lemur Microcebus murinus and the Golden-Brown Mouse Lemur, M. ravelobensis), in their natural habitat to understand their current ectoparasite diversity, possible effects on lemur health and potential intercepts for disease transmission between species.

The Grey and the Golden-Brown Mouse Lemur have been studied for over 20 years in the Ankarafantsika National Park in northwestern Madagascar by our international team and a lot is known with regard to their behavior, habitat use, communication and sociality. We know, for example, that the Golden-Brown Mouse Lemur sleeps in groups, whereas the Grey Mouse Lemur was found resting predominantly alone in our study. Considering the fact that mouse lemurs are designated “marathon sleepers”, who can easily spend more than 17 hours asleep, this social difference might well be one of the influencing factors affecting ectoparasite infestation.

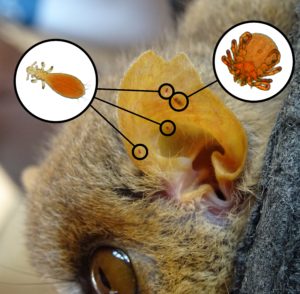

So far, a systematic investigation on ectoparasite infestations and evaluation of potential influencing factors over an extended period were lacking. We first of all found that individuals of both mouse lemur species hosted sucking lice, ticks and two species of mites.

The two mite species collected in our study could not yet be identified to the species level, as there are no reports of comparable mites infesting mouse lemurs. More surprising was the fact, that collected lice and tick specimens, even though they were morphologically similar to previously described species, showed distinct differences when comparing them based on genetic information. These findings highlight the value of additional genetic analyses, especially when trying to identify possible pathways for disease transmission. Are we actually dealing with the same ectoparasite species on two different host species, or is there a natural barrier which the parasite cannot cross?

Our findings furthermore suggest that the degree of sociality at the hosts’ sleeping site and related social grooming between members of a sleeping group affect the risk of ectoparasite infestation. We also found significant seasonal variations in ectoparasite occurrences which need to be kept in mind when planning, conducting or comparing studies in the future.

This spring, a large die-off of Sifakas (a larger lemur species) was observed in a private reserve in the south of Madagascar, possibly due to a parasite or tick-borne disease. In one part of the Ankarafantsika National Park, close to our study site, our team furthermore observed a potentially alarming population decline in the Golden-Brown Mouse Lemur. This emphasizes the importance of a comprehensive investigation of the current host-parasite interactions, to identify potential threats and pathways for pathogen transmission.

Good article