The recognition of the increasing emotional significance of relationships between people and animals takes on particular salience for people living with a long-term mental health conditions. Demonstrated benefits from pet ownership include reduced stress, improved physical health, increased social interaction and reduced loneliness. Loneliness and isolation are key concerns for those living with mental health problems and having a support network in place is important for living everyday life. During difficult emotional periods people report losing relationships with friends and family as well as connections with valued activities which maybe difficult to reconnect with. Emphasis is often placed on the importance of family, friends and interaction with other people. However, the role of pets within this support network is relatively under explored.

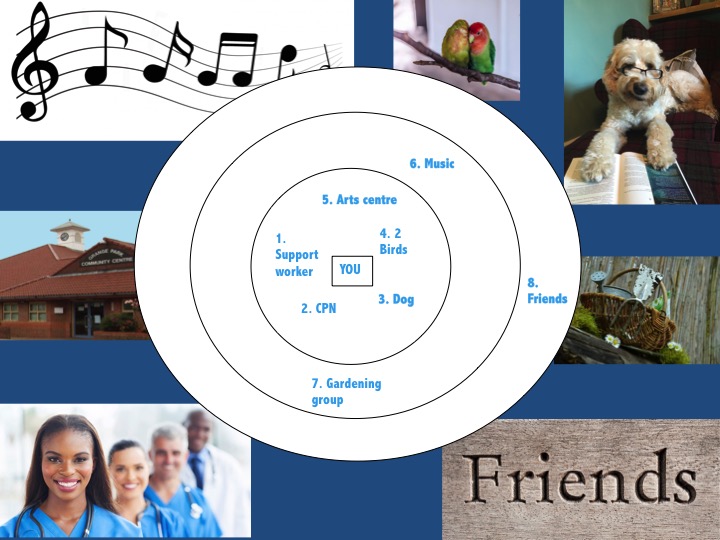

We examined the role of pets within the personal communities of those living with a mental health condition by analyzing interviews with 54 participants, 25 of whom had a pet. Participants were asked to map personal networks using a diagram, which consisted of three concentric circles. Interviewers started the interview by asking ‘Who or what do you think is most important to you in managing your mental health?’

Participants could place network members in either the central circle considered most important, the middle circle, considered important but not as important as the central circle or the outer circle, considered important but not as important as the two more central two circles. Identified network members included friends, family members, health professionals pets, hobbies, places, activities and objects.

The majority of pets were placed in the central, most valued circle of support within network diagrams. Pets were of increased importance where relationships with other network members were limited or difficult.

Pets were implicated in the management of mental health through the provision of secure and intimate relationships not available elsewhere. Given the consistency of presence and a close physical proximity, pets were an instant source of calming, therapeutic support for their owners.

“So with my pets I suppose although my Mum and Dad are very significant figures they’ve also got their own lives and lots of other things going on so I’m only one aspect of that life and I feel that the pets I suppose they depend on me and also I have daily contact with them and they also give me a sense of wellbeing which I don’t get from any [one else] because most of these interactions with my Mum, Dad, [friend], are all by telephone rather than physical contact and that’s the big difference is the empathetic physical presence”. (ID 21, 10 birds, first circle)

I feel that the pets I suppose they depend on me and also I have daily contact with them and they also give me a sense of wellbeing which I don’t get from any [one else]

Pets helped their owners manage feelings by distracting them from symptoms and upsetting experiences such as hearing voices and suicide ideation and provided a form of encouragement for activity.

“But if I’m here and I’m having…having problems with voices and that, it does help me in the sense, you know, I’m not thinking about the voices, I’m just thinking of when I hear the birds singing” (ID 2, 2 birds, first circle)

Participants in this study had more difficult relationships with others and experienced greater levels of stigma than those included in a study exploring the role of pets in the management of chronic physical conditions.

“I think it’s hard really when you haven’t had mental illness to know what the actual experience is for someone who has had the experience. There’s like a chasm, deep chasm between us – a growing canyon. They’re on one side of it and we’re on the other side of it. We’re sending smoke signals to each other to try and understand each other but we don’t always”. (ID 1, 1 cat, first circle)

There’s like a chasm, deep chasm between us – a growing canyon. They’re on one side of it and we’re on the other side of it.

Pets helped their owners to manage this stigma directly by providing acceptance without judgment.

“But he, his [the cat’s] love for me and acceptance of me never changed”. (ID 7, 1 cat, second circle)

Participants described the various, different ways that pets connected them to others in, and beyond, their personal networks or to the wider social environment.

“You know, so in terms of mental health, when you just want to sink into a pit and just sort of retreat from the entire world, they force me, the cats force me to sort of still be involved with the world”. (ID 5, 2 cats, first circle)

Having two dogs myself, I can certainly identify with the characteristics attributed to pets in our study. I very rarely get down the road now without a neighbor or friendly stranger stopping to ask me about them and it’s true what they say that ‘there’s nothing better to come home to than a dog’s welcome’.

I was surprised though by the range and depth of roles pets played in the management of mental health problems from the perspectives of participants. Interestingly, for the people included in this study despite their potential value, pets were also not considered or included in discussions about their mental health care.

Given that service users currently feel distanced from healthcare and uninvolved in discussions about services generally, taking more creative approaches to service provision including the discussion of pets, may be one way of addressing this because of the value, meaning and engagement that individuals have with their pets.

We think that our study provides the mental health community with possible areas to target intervention and potential ways in which to better involve service users in service provision through the discussion of valued experiences.

Acknowledgements:

This is a summary of independent research funded by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR)’s Programme Grants for Applied Research Programme (Grant Reference Number RP-PG-1210-12007) and the National Institute for Health Research Collaboration for Leadership in Applied Health Research and Care (NIHR CLAHRC) Wessex and Solent NHS Trust. The views expressed are those of the author(s) and not necessarily those of the NHS, the NIHR or the Department of Health.

Comments