You can also listen to Dave’s podcast Palaeocast where he interviews one of the authors:

You can also listen to Dave’s podcast Palaeocast where he interviews one of the authors:

During the Permian period, some 291.6 (± 1.8) million years ago, the city of Chemnitz, Germany, was an ‘oasis’ in the middle of a semi-arid landscape.

Only 15 million years earlier, in the Carboniferous period, extensive coal forests and swamps had covered huge areas of the planet. These ecosystems ultimately collapsed due to climate change and only vestiges of them persisted into the Permian.

Wetlands became wet spots, continental forests became isolated islands and the lycopods (club mosses), so dominant in the Carboniferous, now were just a minor constituent of a new composition of forest.

Chemnitz represented one particular Permian wet spot; an isolated island of forest composed of tree ferns, seed ferns, calamites (horsetails) and cordiatales (early conifers). There was still no ground cover as of yet, so the rich red soils lay bare; just a few small ferns grew amongst the aerial roots of the larger trees and the fallen deadwood trunks. Preserved within the tree rings and sediments is evidence of seasonality, thus revealing a rich and dynamic ecosystem.

Within the forests was recently discovered evidence for animal life. Small terrestrial gastropods were found in association with the tree roots and deadwood. Articulated skeletons of amphibians and reptiles with skin impressions are preserved.

The giant millipede Arthropleura snaked its way through the forest and a whole host of arachnids stalked the forest floor.

Amongst the newly-discovered fauna, it is perhaps a pair of scorpions that yield the most insights.

Amongst the newly-discovered fauna, it is perhaps a pair of scorpions that yield the most insights. Scorpions have a long fossil record, going back as far as the Silurian period, but their occurrences as fossils are for from homogenous throughout this time.

The Carboniferous period is particularly rich in fossils, having yielded over sixty described specimens with representatives of both primitive and ‘modern’ lineages. By contrast, the Permian period is practically void of fossils, with just a couple of trackways and a single occurrence of some leg fragments preserved.

The scorpions preserved at Chemnitz belong to a more primitive group, indicating that like the lycopod trees, they were able to persist into the Permian, beyond their heyday in the Carboniferous.

The scorpion couple

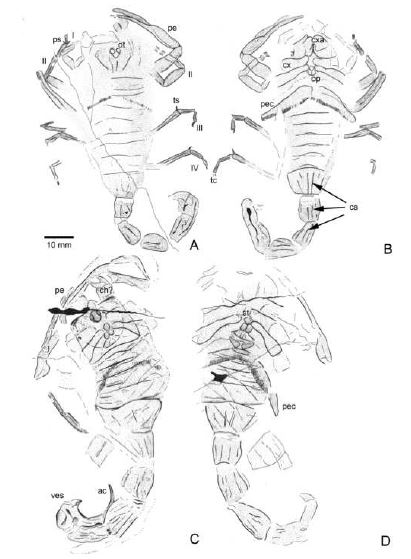

The two scorpions preserved at Chemnitz are of the same species, ?Opsieobuthus tungeri, and of similar size, but show subtle differences in their morphology. This is most evident in their pectines, the comb-like structure on the underside which is a terrestrial adaptation for prey/mate detection and general olfactory orientation.

Usefully, the size of the pectines can be employed to infer the sex of a scorpion since a male will typically have more numerous and longer ‘teeth’ on his ‘comb’ than the female. In this instance, a slightly longer and thinner comb with more teeth can be observed on one specimen, suggesting it is male. The authors named that individual Jogi and the other specimen, lacking the distinctive male characteristics, was named Birgit.

Whilst the distinction of sex within this pair of scorpions is impressive, it is perhaps the position in which they were preserved that really gives a tantalising glimpse into their palaeoecology.

The two specimens were discovered in close proximity to each other (about 2m), but Birgit was discovered within a burrow, surrounded by other fragments of scorpion exoskeleton, whilst Jogi was preserved on the forest floor. Considering how large scorpions would often keep a distance from each other, the inference is that Jogi and Birgit were a mating pair.

Their differing locations, with Birgit inside of a burrow, further suggests that Jogi might have been ‘mate guarding’ Birgit. This behaviour is something we can observe in some modern scorpions today. The male, upon discovering a sub-adult female will guard her until she reaches her final moult and maturity.

A volcanic eruption

We can only speculate as to the level of security Jogi had expected to be able to have provided Birgit, but guarding her from a rhyolitic volcanic eruption was probably beyond his capabilities.

This volcanic eruption first started with a blanket of ash that smothered the forest, gently covering everything in life position like a thick snow. A subsequent explosive eruption went on to violently flatten everything above the ash layer, much like how the 1980’s eruption of Mt St. Helens levelled all the trees in its vicinity. The ash layer was responsible for the death of all the organisms at ground level, but allowed for their exquisite preservation and even protected them from the following explosion.

The trees are still rooted into the soil where they once grew, deadwood still lies on the forest floor in the position where it once fell and Jogi is still waiting for Birgit to emerge from her burrow.

The result is that the forests in Chemnitz are preserved as a ‘T0 assemblage’, meaning all the organisms preserved are in situ. The trees are still rooted into the soil where they once grew, deadwood still lies on the forest floor in the position where it once fell and Jogi is still waiting for Birgit to emerge from her burrow.

Insights into the Permian period

On the whole, terrestrial fossils are notoriously rare from the Permian period and so the fossil forests found at Chemnitz are doubtlessly our closest approximation to a complete terrestrial ecosystem during this time.

The recent discovery of Jogi and Birgit was made in a 24m by 18m excavation within the city. This small, hand-dug excavation also revealed a remarkable 53 fossil tree trunks, all in life position, as well as all of the animal life we know from the locality thus far.

Given that the rich fossil forest expands across the entire city, who knows what other fantastic insights into the Permian period might lie just beneath the surface.

Comments